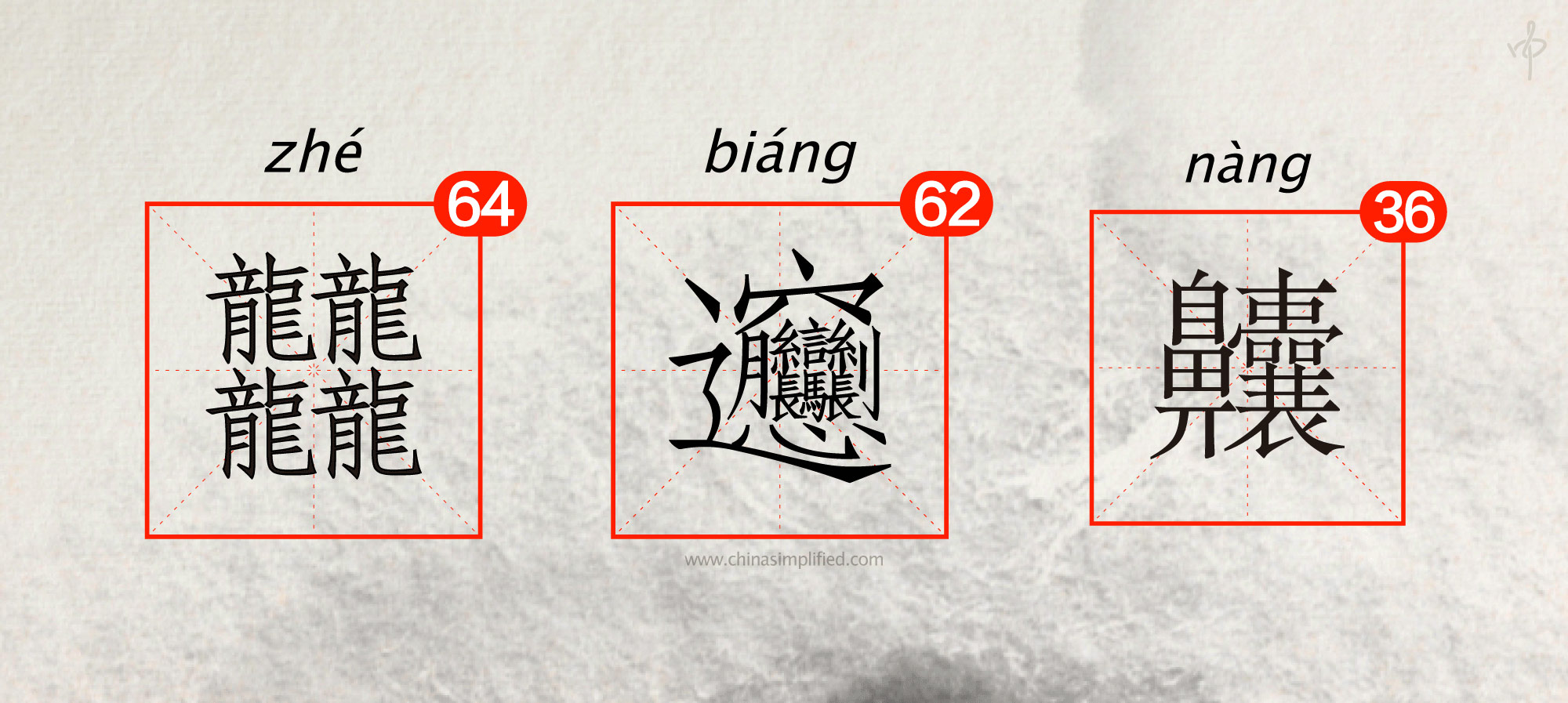

The character biáng requires 62 total strokes to write and contains a 馬 horse, 月 moon,刂 knife and 心 heart plus other radicals. Biáng doesn’t exist in Modern Standard Mandarin which only serves to increase the mystery and intrigue surrounding the character.

Among competitors for hardest character, the traditional zhé character meaning “verbose” or “scary” contains four dragon radicals and wins for cool factor, though its 64 strokes comprise four 16-stroke copies. The nàng character which means “having a stuffy nose” or “speaking with a nasal twang” earns points for complexity and for somehow hanging onto its place in the modern dictionary.

One version of the biang story shows how even native Chinese speakers can struggle writing the tougher characters:

There was once a young Chinese student wandering past a Shaanxi noodle shop around lunchtime. He heard people inside saying “biang! biang!” and feeling hungry entered to see for himself.

The student watched the cook pull long strings of noodles and serve fresh bowls to satisfied customers. Excited, he asked for one. After scarfing down the bowl, he realized he had no money to pay the bill. Sensing trouble with the cook, the student thought fast.

“What do you call your noodles?” asked the student.

“Biang biang mian,” replied the cook.

“Do you know how to write the character biang?”

The cook scratched his head, having never thought about it.

“Then I’ll teach you how and my noodles are free!”

Before the cook could protest, the student grabbed some paper and wrote a character so complicated that everyone in the restaurant burst into applause. Grinning at being taken, the cook tore up the student’s bill.

The cook’s noodles soon became legendary and the word biang came to mean the sound of someone falling down and feeling surprised, just like the first time Homer Simpson bumped his head and exclaimed, “Doh!”

In other common versions of the story, biang comes from the sound of a cook slapping noodles against a table, or the chorus of people munching the noodles. Less important than the origin of the story is what it says about the language and culture.

Professor Victor Mair of the University of Pennsylvania in his Language Log post explains it well:

“For me, biang symbolizes the difficulty of accommodating the full fecundity of folk, popular, and local/regional cultures and languages within the bounds of the standard writing system, which enshrines the elite, high culture, and now also the bourgeois, urban, national culture. In other words, biang is well-nigh bursting at the sides of the scriptal and phonetic boxes within which it is constrained.”

Not bad for a character that likely sprung from the tangled imagination of a noodle cook centuries ago in Shaanxi China. Biang is hands down the hardest Chinese character. And fortunately for us, every character we encounter in the future will seem easy by comparison.

Give it a try!

- Try writing the biang character.

- Take a picture of you and your masterpiece.

- Tweet it to us @ChinaSimplified or upload it and tag us on Facebook or Google+

The lyrics to “生僻字” have a lot of great characters, like 魃魈魁鬾魑魅魍魉 and so on and so forth

Hi i’m Pixel and the strokes that biang has is only 58 and is only CONSIDEDERD the hardest to write. People actually say that nang is the hardest one to write but i agree that biang would be the hardest to write.

It is zhe and zheng. They have 64 strokes while the 2nd hardest to write is the biang.

P.S. They are simplified

The traditional chinese biang has 58 strokes

I also wrote with my own hands.

The real one Huang (172 Strokes).

What does huang mean

It has an unknown meaning

That is traditional chinese

I’m very curious to know how all these different characters used inside this complex character produces the sound “biang? how do all these different characters end up making one word?

I think you’ll know the answer to your question after reading the article.

it just looks like the characters are in the word. the characters don’t contribute to the overall pronounciations of the word.

我不明白

how u not geti it hayaa

不可以用键盘类型

lololololololololololololololololololololol THE HARDEST CHINESE WORLD IS BIANG!

At least China has a millenial written language.

English doesn’t even have a written language. It stole Latin letters to write the simplest language in history. So simple anybody can speak (spit) it.

Good points and funny af

This doesn’t make any sense as an argument.

The language that Oracle Bone Script (the earliest extant version of Chinese characters) represented bore no resemblance to modern Mandarin. Thousands of languages all over the world use a version of Latin script – how on earth does that mean they “don’t have a written language”?

English is far from the simplest language in history – it’s got the highest vocabulary of any language in the world, at well over a million words. Mandarin Chinese, for one, is a far simpler language – particularly in grammar, where it’s got one of the simplest grammar systems of any major language (though this is far from an insult – simplicity in languages is a sign of refinement, according to linguistic science.)

I take it from your emojis that you’re from Latin America. I am sorry that the US has ruthlessly exploited your brethren and plundered the wealth of the Spanish-speaking parts of the Western hemisphere. I’m a socialist too, as any half-decent human being should be. But don’t take your frustrations out on the English language – it’s not at fault, even if some of its speakers are.

more than 1000 Chinese letters are stolen from Japanese,

or

every Japanese letter was stolen from Chinese?

Japan stole the Chinese letters as they actually used to be a part of China but split many years ago

Ugh, why pretend you know something you don’t?

Chinese doesn’t have letters. It has characters.

Japanese uses chinese characters, which they call 汉字, pronounced”kanji” in Japanese and “hanzi” in chinese. 汉 refers to the han ethnic group in China, and 字 means “writing”.

How did they steal Chinese writing when they still call it chinese writing?

Japanese has two alphabets of their own crration. One for Japanese words, and one for foreign and onomato paeic words.

Japanese writing is a combination of all three writing systems into one system.

And no, Japan has never been part of china. That’s like saying England used to be part of France. 🙄

Uhm, there’s actually some Asian languages that used Chinese and incorporated into their language. For example Korean and Japanese, most of the characters in there are Chinese. A lot of Japanese culture is kind of based off of China’s because they were continuously fighting China in the past just to get a hold of the things they had.

By that reasoning, Spanish doesn’t have a written language, either. The Romans are from Rome, in Italy. Not Spain. Spain was conquered by Rome. So the written language you are so proud of is someone else’s. 🤣🤣🤣

It’s not. The hardest chinese word that I am aware of is huang. I has 172 strokes

Well I wrote it with my own hands!

thats actually pretty cool

This is a hard word, though there must be something harder 😊

biang!!!!!!!!!!!

:, = 😏

你不知道中文?😶 why are you reading this if you don’t know chinese? well whatever.

I know Chinese

爨齉龘䨻搎澅 🙂

爨齉龘䨻搎澅

.what

.

(what) for what do you mean?

齉

Sm

林泓玮

覈

I don’t think the word ‘搬’ is a hard one, is it?

No

I Like the complexity of this specific word. I discovered it by chance in Indonesian language, a reference meaning pure blood.

And what word is it in Indonesian language that means pure blood? Do you mean Biang?

I think the Pinyin Biang is pronounced as phiang. And the word Piang in Indonesian language means snack made of sticky glutinous rice.

um well biang is pronouced: beeang (kinda i cant explain i only can write the pin yin… not how to pronouce it :, )

雪花飘飘北风萧萧 天地一片苍茫

Does鬮,龖,龗and蘒exist?

齉 lol

So I’ve been asking people what they think the hardest Chinese word to write is and none of them knew of this word. It’s so obscure these days… but so fun to learn.

The other replies were 懿, 鬱, 體, 魑魅魍魉, and 搬.

搬 is hard! Oh gosh…. I learned it when i was…. 8 i think 😐

Fuck you it is not hard

I think that’s what Chen is saying, Chloe. Calm yourself…!

I learned this word at 6

yeah LOL😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂 I kind of agree

Im 8yrs old and Im learning Chinese

Such a foul

Fuck you, cunt flaps!